Osmanthus syrup and sticky stuffed lotus root 蜜汁藕

A trendy restaurant in Hangzhou that only serves lotus root. Plus, a recipe for stuffed lotus root

The new year may be here already, but preparations for The Real New Year Festivities (aka lunar new year) have only just begun. Spirits have not sunk into bleak January realities yet— for Chinese people these next three weeks are merely a respite, a readying for more qifen and a gleeful continuation of holidays. I wonder if it’s possible to burn out on celebrating.

At least the inflatable Santas astride various balconies and windowsills in Shanghai are gone, thank god. Red paper lanterns have gone up around shopping malls. Last week someone left a potted citrus/mandarin tree outside the door of my apartment building and it’s still sitting there, either a forgotten delivery or a communal decoration. Are the fruits on these actually edible? Someone let me know.

One of my favorite festive dishes is sticky rice stuffed lotus root with osmanthus syrup. I went into a bit of a deep-dive on lotus root after my trip to Jiangsu last month.

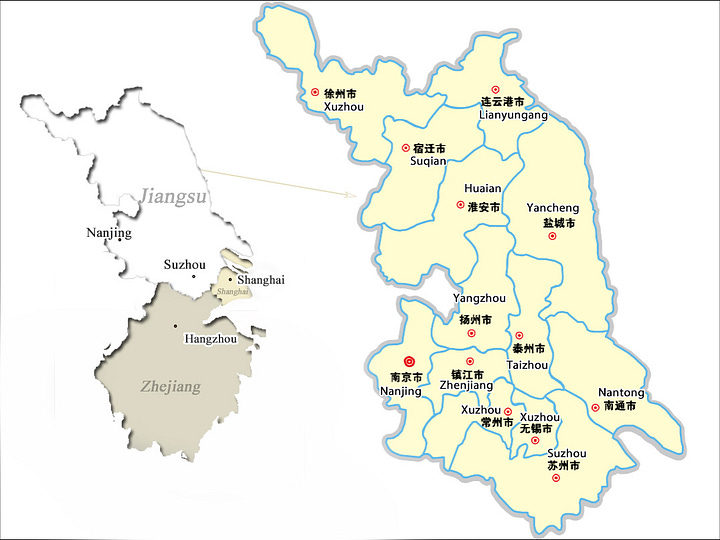

Winter is the season for harvesting lotus roots in the Jiangsu/Zhejiang region. You may only be familiar with the snappy, crunchy texture of lotus roots, and I did eat those here, stir-fried and tossed in chili oil-laced liangban salads. Fresh lotus roots are so sweet and crunchy you can actually eat them raw.

But there are also other parts to the lotus plant. The leaves, seeds, roots, and starch are used most often in Chinese cuisine.

The dry-textured, crinkly round leaves are extraordinarily fragrant, used to wrap sticky rice and fillings for steaming

The starchy seeds can be eaten fresh, but since they’re highly perishable they’re most often dried. They have a subtle vegetal sweetness and can be cooked in soups, or steamed and mashed into lotus seed paste for buns.

The rhizome/stem portion is also called the lotus root. With their pattern of holes, you can slice them cross-wise and stir-fry them with aromatics (scallion, chiles, garlic), blanch them and toss with a vinegary sesame oil soy sauce dressing for a cold dish/salad, cut them into potato-like chunks for stews and soups, stuff with sticky rice and serve with osmanthus syrup, or grind up and fry into balls.

The starch is collected by grinding lotus root into a paste, filtering the pulp through a thin cloth and drying the sediment in the sun into flakes. Called lotus root powder, oufen 藕粉, it’s a quick breakfast food, often mixed with hot water for an instantly thick and glossy soup.

You can cultivate lotus roots anywhere, as long as you have nutrient rich mud, lots of water and warm summers. Sichuan, Yunnan, and Jiangsu all have their own lotus root varietals. Hubei province and the Honghu area, in particular, with its subtropical monsoon climate and flood-prone wetlands, is responsible for a third of the country’s lotus root production. And you don’t even need a lotus root pond— you can even grow them at home, in a pot (yes, I’m gonna try this).

In Zhejiang, the Xihu (West Lake) in Hangzhou is naturally thick and verdant with lotus plants. I visited in December and missed out on the flowering season, but the lake was still gorgeous. When the leaves wilt and the seeds pods dry out, it’s an indicator to start harvesting the snaking roots from the mud bed.

In Nanjing, I came across a restaurant called 藕韵 OUYUN. This chain started in Yangzhou and soon expanded to five locations, with two in Nanjing. The restaurant serves only lotus root specialties, mostly from the Jiangsu/Zhejiang region.

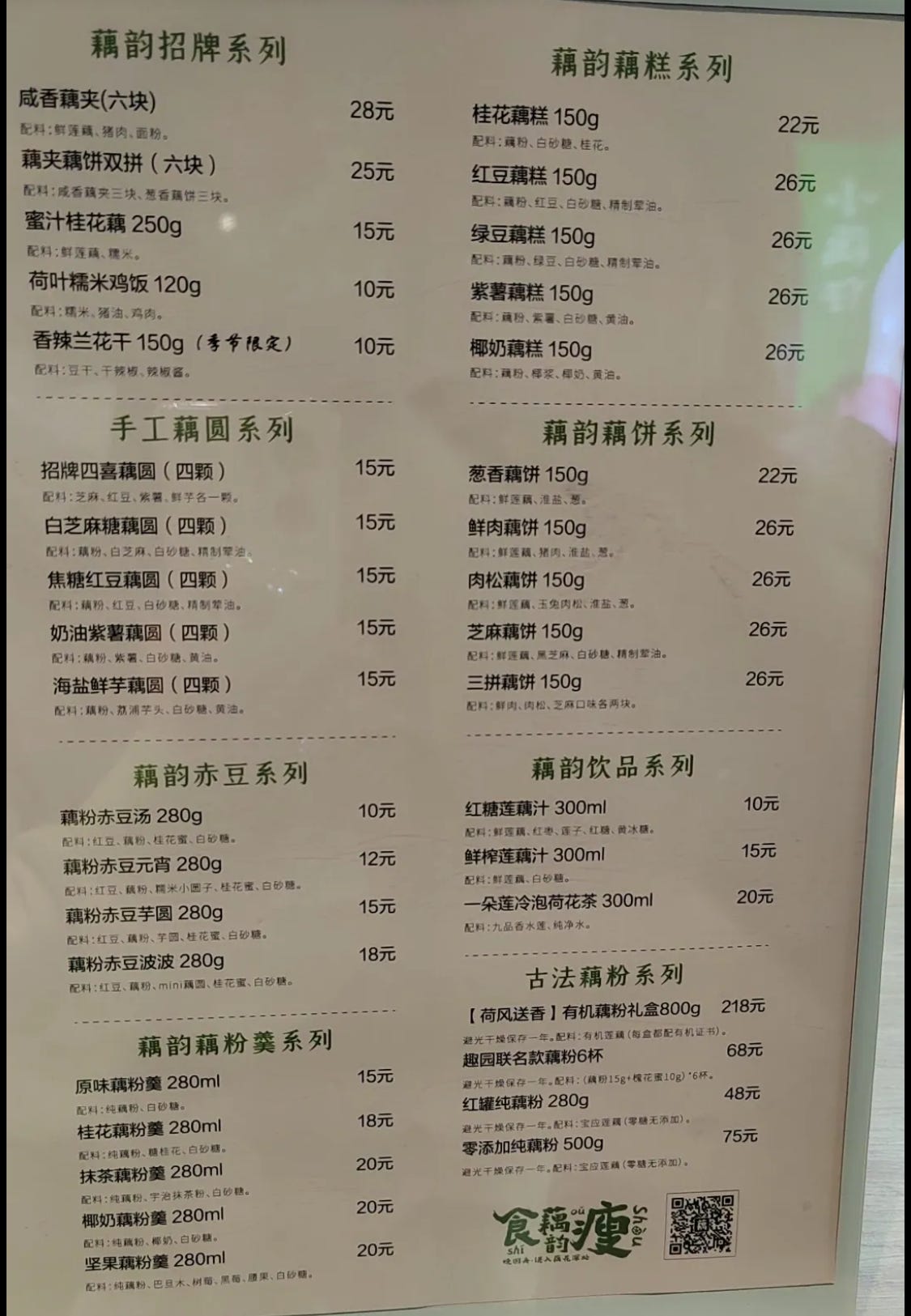

Take a look at the menu.

Many of these dishes focused on lotus root starch, which provides a jelly-like, bouncy texture to desserts and a smooth, glossy viscosity.

The categories, translated:

Ougao 藕糕 is a soft, steamed confection with a bouncy chew (similar to those made with tapioca starch). I ordered osmanthus, although you can also pick the red bean, mung bean, purple sweet potato, and coconut milk flavors.

Ouyuan 藕圆 are semi-translucent balls made of lotus starch, similar to glutinous rice balls. You could pick black sesame, caramel and red bean, butter purple sweet potato, or sea salt taro filling.

Oubing 藕饼 are fried and battered lotus ‘sandwiches,’ either savory, stuffed with scallion, pork, or pork floss, or sweet (black sesame).

Oufen geng 藕粉羹 is a gorgeous lotus starch-thickened soup. This came either unsweetened or with osmanthus blossom, matcha, or nuts with dried fruit and raisins.

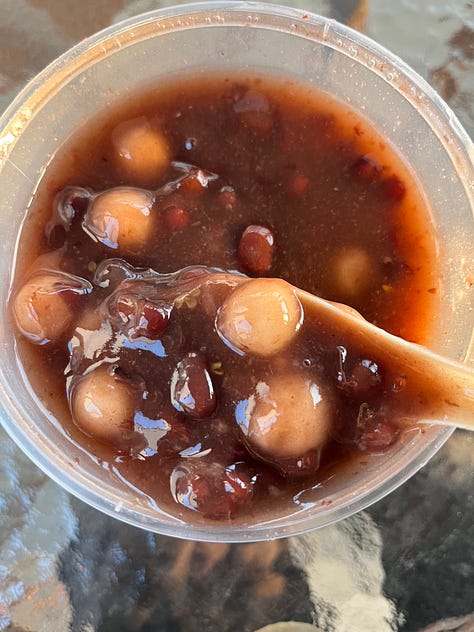

Oufen chidou 藕粉赤豆 featured red beans, tapioca pearls, chewy taro baubles (yuyuan), and osmanthus blossom. This is a thinner, more drinkable lotus starch soup.

Ouzhi 藕汁: freshly pressed lotus juice, and a warm lotus tea steeped with brown sugar and jujube date.

You’ll notice osmanthus (guihua), those tiny yellow flowers, in almost every sweet dish. Osmanthus and lotus root go hand-in-hand; the blossoms have a delicate sweet flavor, smelling of honey and apricot. Some describe it as a champagne aroma with notes of gardenia and ripe peach.

It’s hard to find fresh osmanthus unless you have a tree, but I love making osmanthus syrup or guihua jiang with dried blossoms. The flavor of osmanthus is light and sweet, without any of the bitterness of most dried flowers. You can drizzle the syrup on desserts, spread it on bread like jam, strain it and use it in drinks, or use the blossoms as a garnish.

I like the 藕韵 OUYUN restaurant because it provides a sampler of many Jiangsu lotus root specialties all at once, but I didn’t get a “wow” moment until a few days later in Hangzhou, when I finally ate the best version of sticky stuffed lotus root in a restaurant called Hangzhou Jiujia 杭州酒家. This was the bite I’d been waiting for.

I’ve always wondered how you could turn something so characteristically crunchy into absolute soft, potato-like butteriness.

The secret? 1) A lot of time and 2) using the correct variety.

I previously thought two hours were sufficient, as long as the rice was cooked. When I asked a vendor in Hangzhou he said sixteen hours of cooking was best, twelve hours the minimum.

Simmering the roots slowly over low heat allows the fibrous root to break down and soften without falling apart and losing integrity, or leaking any of the sticky rice inside. He starts prepping the lotus root at 6am in the morning, and serves it the following morning.

Also important is the variety. Lotus roots are divided into two categories, cui’ou 脆藕 (snappy, crunchy) and fen'ou 粉藕 (starchy, meaty).

The crunchier baihua’ou are identifiable by their length and thickness: the segments are narrow, elongated and sometimes ridged, called “seven hole lotus” 七孔藕 or field lotus 田藕 (you can grow it in shallow water). The skin is smooth to the touch, not rough, and the white flesh is crisp and juicy, best for stir-fried dishes and salads.

Honghua’ou have round, fat segments that contain more starch and less water than baihuaou. The skin is more textured, a light tan color with dark flecks and mottles, and the segments tend to be thicker and shorter (this variety is often nicknamed “nine hole lotus” 九孔藕). Identifiable by its pink flowers, this variety grows in deeper ponds and lakes, and is often found in the wild. Since it cooks down into a meaty softness, this is the variety of choice for slow-cooked lotus root, stews, and soups.

This week’s recipes: one free and one for paid subscribers.

Osmanthus syrup 桂花酱

This syrup is wonderful. If you’re in the US, you can get dried osmanthus either at an Asian grocery store or online. I’ve tried quite a few brands from Amazon— some were old as dust, flavorless and awful, but I keep returning to this one, it’s pretty fresh and has a great aroma.

Makes about 1 cup

1 cup (200g) granulated sugar

¾ cup (180g) water

2 tablespoons (28g) lemon juice

¼ cup (8g) dried osmanthus flowers

Pinch of salt

In a small saucepan, combine the sugar, water, and lemon juice and bring the mixture just to a boil over medium-high heat. Cook until the syrup is slightly thickened, about 3 minutes. Add the dried osmanthus and salt and reduce the heat to low. Whisk to incorporate the flowers, cooking until the syrup begins to bubble around them, about 2 more minutes. Remove the syrup from the heat and let steep until cooled, then transfer to a clean glass jar, screw on the lid, and store in the fridge. The syrup is thin but will thicken as it cools, and its osmanthus flavor will also intensify over time. Keep in the refrigerator for up to three months or even longer.

Sticky stuffed lotus root 蜜汁藕

with lemon and candied hazelnuts

This traditional delicacy is often sold on the street as a snack, but also makes an appearance at banquets. It’s an enchanting Shanghainese side dish, glossed with a lacquer of syrup, and cut into slices to reveal the cross-section of molten sticky rice.

TIPS: