Last week, I recorded a podcast episode with Todd Schulkin from the Julia Child Foundation for “Inside Julia's Kitchen,” a show on the Heritage Radio Network. We talk about veganism and Chinese food, the IACP award and grant, recipes from my cookbook, my “Julia moment,” Yunnan, and more. Listen to the episode here (and pardon my pre-dawn voice/brain)

Recently I’ve been thinking a lot about textures. In particular, this pair of Chinese words:

细腻 xi ni

1) adj. (texture) Fine and smooth; satiny; delicate.

2) (performance or craftsmanship) Finely detailed; subtle; exquisite; meticulous.

粗糙 cu cao

1) adj. (texture) Rough and coarse.

2) (performance or craftsmanship) Crudely made, of poor workmanship, slipshod.

Taken literally, they describe smoothness or roughness. A cashmere sweater is xini, a wool sweater is cucao. A polished jade is xini, a sedimentary rock is cucao. A fine pastry is xini, coarse cornmeal is cucao. You get the idea. For the Chinese palate, the finest foods are slippery and silky, gentle and gelatinous, chewy with resistance perhaps, but never tough. Part of the cooking process is breaking down an ingredient and bringing out its finest textures. Even raw vegetables are tenderly cut and slivered with the finest care, into whiskers and threads that dance in the spicy acidic lift of a dressing.

The interesting thing about these two adjectives is that they apply metaphorically to people and temperaments as well. A person who is xini is sensitive and emotionally aware, noticing changes in a friend’s mood or subtle shifts in their social environment. Someone who is cucao is shallow and crude, without emotional sensitivity, or lacking in refinement and good taste. When looking up the definition of 粗糙 cucao, I stumbled upon an article that lamented “the modern cucao life.” In our present day we’ve all become rougher, the author said. The ancients didn’t have the same material resources, but they lived more simply, they were more sensitive to seasonal changes and daily, domestic textures. How’s that for a third layer of meaning.

A few weeks ago I asked my friend June to taste a sauce I made from a gnocchi recipe in a Western cookbook. It was supposed to be this spring-forward, bright green purée of sautéed peas, spinach, mint, and lemon juice.

“Nice flavor,” June said. “However, I feel like a cow chewing its cud.” I burst out laughing.

The issue with a purée, to her critical Chinese palate, is that it lacks technique and refinement. No matter how powerful your blender, a pea purée tastes like puréed peas, there is no magic of transformation. It might even be inferior in texture (she’d prefer eating the spinach or peas whole, with their slippery, tender bite.)

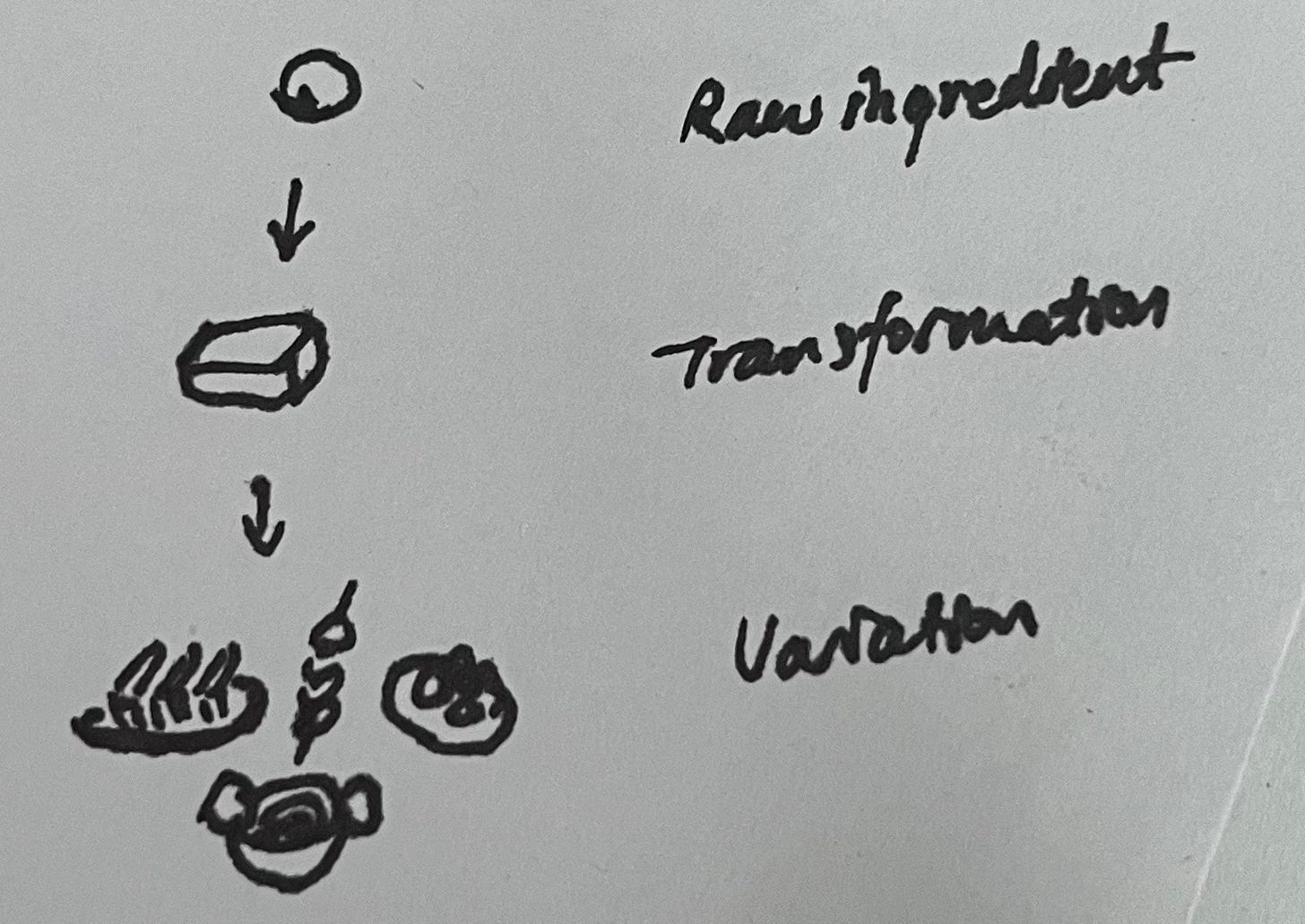

In many Chinese staples, laborious processes like drying, hydrating, grinding, water-milling, pounding, and straining transform the coarse, grainy, and fibrous textures of beans and grains into more refined mouthfeels: moist (爽), soft (软), tender (嫩), slippery (滑), bouncy (弹), gelatinous (胶) and sticky (粘). Corn, sorghum, black rice, glutinous rice, and millet are ground into flour or cooked into moistening porridges. Mung beans and red (adzuki) beans are cooked and smashed into rich and luxurious sweet bean pastes, light and crumbly enough to fill the flakiest pastry. Rice is pounded into sticky doughs and smooth, chewy rice cakes, like Ningbo niangao and Yunnan erkuai, blank staples ready for variation— they can be cut into slices and batons, boiled, grilled, or stir-fried in a wok.

Tofu is the ultimate example of textural transformation. Soybeans contain high amounts of fiber and raffinose, which makes them hard to digest and causes flatulence, so Chinese people turned the bean into soy milk and coagulated it into tofu, which is infinitely more versatile for cooking, gentle in texture, and easy on the gut. The yellow split pea, one of the most widely consumed dried beans in Yunnan, is treated in a similar fashion.

Outside the north city gate market in Dali, my favorite breakfast vendor sets up a tent every Tuesday to Sunday, serving bowls of porridge and noodles at low tables.

I order a bowl of xidoufen, pea porridge, ladled from a large pot held on a stove. Unlike a rice congee, there’s no trace of grain in this glossy glop of starch and protein— it’s thick, hot and opaque. I barely have to chew. A buttery, rich pea flavor unfolds, a mysterious presence without any pea fiber. I slurp down the porridge and feel my stomach warm and my face flush. The porridge moistens my parched throat. Suspended in the soup are crunchy bits of pickled chile peppers, sour cabbage, salted fermented radish, toasted sesame seeds and fresh bright herbs. Dark streaks of vinegar and chili oil swirl in the cilantro-dotted galaxy. I dip in a youtiao— a fried yeasted dough stick—and the porridge clings to the hollow crevices like a sauce.

In Yunnan, pea porridge comes with many variations and toppings, distinct to each town or village. It’s a humble worker’s breakfast: a bowl cost 8 RMB, about a dollar. The meals fills your stomach and gives you energy, without the heaviness of wheat or rice. Satiation and protein with a low glycemic index.

Turning split peas into pea porridge is similar to tofu-making. You begin with the whole peas, pisum sativum, pebbly round beans that are dried in the sun and stored in sacks. After soaking overnight, the peas split into yellow halves and loosen from their filmy skins. Like making soy milk, you grind the beans (either with a stone mill or industrial grinder) into a pale slurry. The most experienced vendors strain the pea milk through cloth three times. The first strain produces the starchiest slurry. When you add water and strain again, you get a thinner slurry. Repeat one more time, a last pass that squeezes any remaining beany goodness out of the dregs.

Add the liquids to a large pot in reverse order, bringing the watery liquid to a boil first, then adding the second slurry and the settled starch last. The porridge will turn cloudy and begin to thicken furiously. Season with salt, and stir constantly for 15 minutes, until the soup is viscous with body, but not yet sticky.

In another variation, you add chewy, starchy rice noodles (er kuai, 饵块). The porridge coats the noodles like a rich sauce.

The second way to eat pea porridge is to cool and set it into a curd called wandoufen 豌豆粉, similar to mung bean jelly. This ‘pea tofu’ requires no coagulant: the slurry solidifies on its own after a few hours at room temperature.

The possibilities for pea curd go beyond the chilled jelly: you can fry it to form a chewy crust and dip it in spices, simmer it in soups, or cut it in cubes and stir-fry it in a wok. It’s similar to Burmese chickpea tofu or shan tofu, which is made with chickpeas, but less waxy and more slick and refreshing, with a thick bean fragrance.

Like a big round cheese or a stone of Arthurian legend, a slab of wandoufen looks like marble but cuts smooth as butter. The server holds the block with one hand and slices the curd like shaving away at a jiggling sculpture. The pieces release and fall into a pile in the bowl. They’re bathed with soy sauce, vinegar, chili oil, ginger juice, garlic oil and a shower of fresh herbs.

Eating pea curd is soundless. The curd isn’t chewy like a starch noodle, it doesn’t squeak against your teeth like tapioca or agar agar or gelatin. You barely even have to chew. The only crunch is from the chopped cilantro and ground peanuts. As you eat your lips purse to catch the drippings of sauce. Your mouth is hot so you eat more to cool it down, but the heat builds. Coolness paired with the thrill of chili oil. Like eating jelly, a bowl of wandoufen makes you feel like a kid again.

Even something humble like pea curd generates infinite variations and ingenious refinements. Some vendors make sheets of guoba 锅巴 by slathering pea slurry onto the bottom of the wok and cooking it to form a golden-brown skin. They scrape off this crust in crackly sheets and layer it between the jelly, which adds a toasty fragrance and gorgeous bands and streaks.

Recipe: Yellow Pea Porridge and Pea Curd/Tofu

Serves 2

If using pea flour:

50g (scant 1/2 cup) water-milled yellow pea flour 豌豆粉 - available in Chinese supermarkets or online here, here or here (note this is different from Indian split pea flour, which is ground dahl, or besan/chickpea flour)

550g (2 1/3 cups) filtered water

3/4 teaspoon kosher salt

If using dried split peas:

50g yellow split peas (here or here) 去皮豌豆 (if split, they are already peeled, if using whole, soak in water and rub off the skins)

Toppings:

Garlic oil, chili oil, soy sauce, toasted sesame oil

Chopped cilantro, toasted sesame seeds, thinly sliced scallion, a sprinkle of each

Youtiao (fried dough stick) (optional), heated and cut into ½-inch rings

If using pea flour: In a small bowl, combine the pea flour and 100 grams of filtered water, whisking until it forms a thin yellow slurry. It’s okay if there are clumps.

Let the slurry sit for 30 minutes. Whisk again until smooth.

In a medium saucepan, add the salt and remaining 450 grams of water. Heat over medium-low heat until it comes to a gentle boil. Add the slurry and whisk to combine.

The liquid will begin to thicken and turn opaque; stir continuously with a spatula. Cook for another 10-12 minutes over medium-heat until the bottom is starting to stick and the slurry ribbons onto itself when lifted from the spatula (should be thick enough to draw visible lines through the porridge).

If using split peas: soak the dried split peas overnight in cool water. Rinse thoroughly and drain. Transfer to a high-speed blender along with 120ml (½ cup) water and blend for 3-4 minutes until smooth.

Pass through a nut milk bag. If using cheesecloth, use a double layer of cheesecloth and tightly ball the top of the cloth, gently squeezing the liquid out. This will be the thicker milk.

Measure out another 120 ml (½ cup) of water and pour it into the solids in the nut milk bag or cheesecloth. Gently squeeze the liquid out. Repeat one more time with another 120 ml (½ cup) water. Combine these two liquids, 240mL (1 cup) total, for the thinner milk.

Transfer the the thinner liquid into a medium saucepan. Heat over medium heat for 5 minutes, stirring continuously. Begin to add in the thicker liquid, a little at a time, stirring to incorporate. Once all the liquid is in the pot, stir for another 10-12 minutes over medium-heat until the slurry ribbons onto itself when lifted from the spatula (should be thick enough to draw visible lines through the porridge).

To make the pea curd/jelly, simply transfer the porridge to a container, cover tightly and refrigerate until solid. Cut into slices and serve with the same toppings, plus julienned cucumber or slivered white radish. Or use the combined sauce below.

For the chili oil sauce - whisk together in a small bowl:

3 tablespoons soy sauce (sub tamari if gluten-free)

½ teaspoon sugar

1 tablespoon Chinkiang black vinegar

3 cloves garlic, minced

1 teaspoon toasted sesame oil

2 tablespoons homemade chili oil, or lao gan ma chili crisp condiment

Great stuff. I have recently been enjoying Burmese (i.e. besan flour-based) tofu recipes, so I'll have to try out this version.

One thing I was wondering was that of the flours linked it seems like first two linked were starches and the Amazon link was not? While this is blasphemy to all the 凉皮 fans out there (including my wife, for whom there is no food in the world more comforting!), I personally prefer the extra solidity that comes from using a flour that still has the protein.