My cookbook was featured in The New Yorker last week! What a thrill to be included on their Fifteen Essential Cookbooks list, among such good company. (You can pick-up a copy of The Vegan Chinese Kitchen here.)

Douhua by definition means ‘bloomed’ or ‘flowered’ soy— soy milk that’s coagulated and then eaten as freshly formed curds, without further draining or pressing. It’s the tenderest tofu you can eat, containing the most moisture.

In English douhua is often translated to silken tofu or tofu pudding. I feel like this captures its texture but not its essence: douhua is newborn tofu, in its uncompressed form, the curds you start with to make all other types of tofu.

1

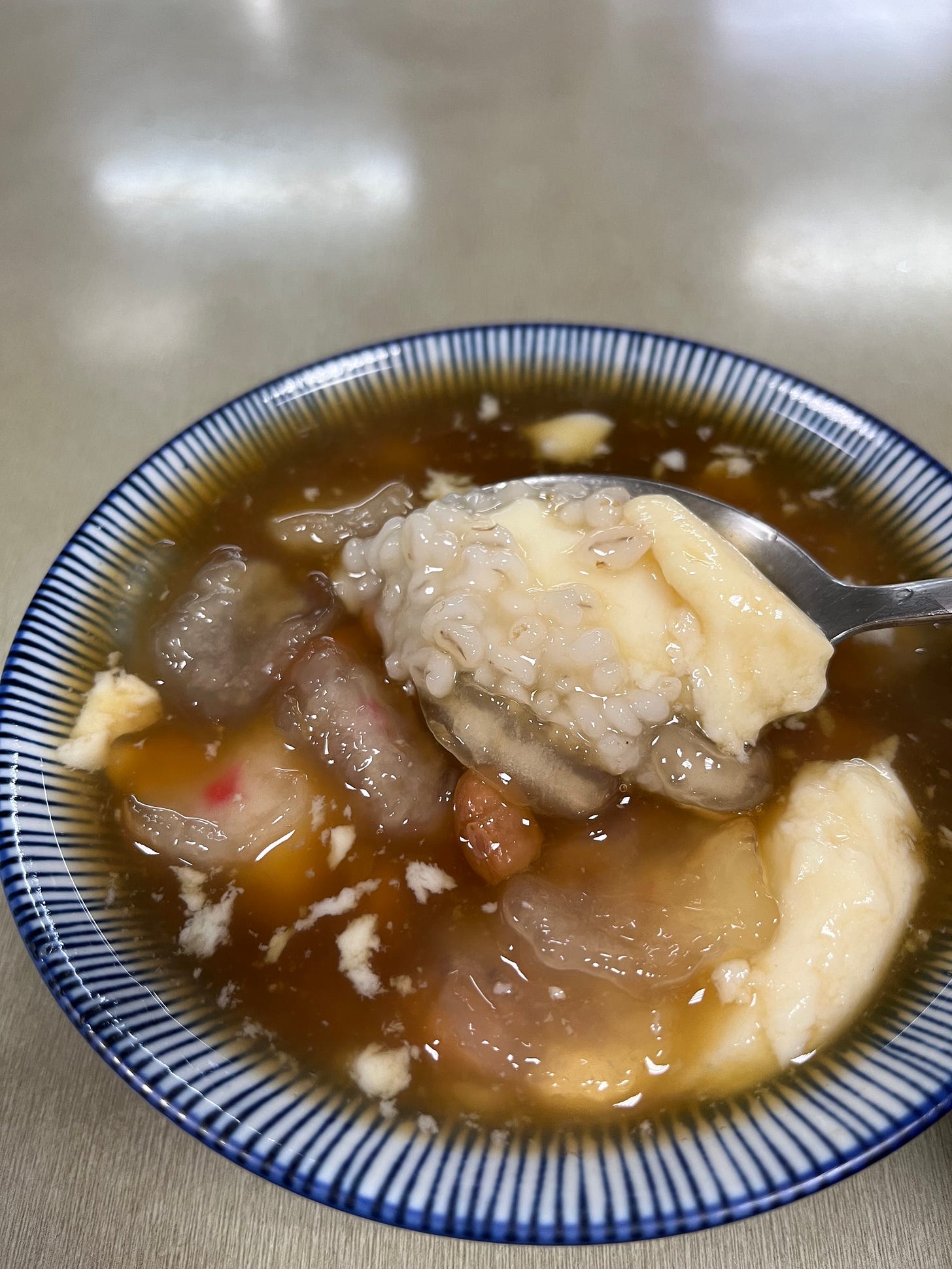

In Taiwan douhua can be dessert, soy milk set with gypsum or GDL into a quivering jello like creme brulee. The essentialists eat it plain with ginger syrup, but where's the fun in that? I load up on the toppings and sinkers, fat starchy beans, chewy taro baubles and coix seed cooked down into a gelatinous tangle. Only soft textures, so as not to confuse the jaw.

On a muggy summer day I ask for douhua with chilled sweetened soy milk, shaved ice and some cooling grass jelly to match the jiggling tofu. This is relief, however temporary. Life may be full of sharp edges but as I nurse the bowl with its sweet soft treasures it feels like everything will be okay.

2

Douhua in Chengdu falls into that curious category of ‘little eats’ (小吃), a quick bite on the street or a snacky meal, like noodles or dumplings. I am immediately overwhelmed by the 70+ options at the breakfast shop, but to the Sichuanese, who eat like food is their local religion, this is basic stuff, merely a prologue to wake up the taste buds and tide you over until the next meal. There’s douhua with sour and hot sauce, douhua with crispy beef mince and pork floss, douhua with fresh noodles (douhua mian) or fried noodles (馓子 san zi).

I order the sanzi douhua. Like everything on their menu this dish is considered fast food, but each bite is mindbending with complexity, flayers layered with sauces and oils that have been perfected for decades. My gentle curd arrives piled with outrageous toppings like an acai bowl on steroids. The ground flecks of Sichuan pepper on top are practically alive, I can hear my tongue buzzing. The chili oil takes over soon, staining everything with its oily slick, lapping the gentle curds with heat. Dark seasonings of soy sauce and black vinegar flavor the broth like a tare. When I taste the tofu I am grateful for its blandness, its cooling effect. It’s the perfect vehicle for bolder flavors.

Sanzi are the crispy things on top, rolled out from a dough of wheat and Sichuan peppercorn water and fried to a golden crunch while stretched out between chopsticks. They're salty and snappy under your molars like a good wonton chip, but slowly soften in the broth, soaking into noodles. Like eating a tortilla strip soup, you appreciate the soggy parts and the crunchy bits in stages.

3

Dessert douhua in Chengdu leaves you wanting more. She’s cold, sweet and dangerous. Bingzui means “chilled and drunken,” the tofu is chilled overnight with sweet rice wine (酒釀 jiu niang), napped with a clear sauce that’s glossy and velvety, thickened with a pea starch slurry. The tofu doesn’t slip or sink, but swims lazily with flecks of fermented rice and koi-colored berries. Each bite is refreshing and cold with a slight winey tang and boozy sweetness.

4

When you coagulate soy milk with gypsum or GDL, you get the most tofu by volume, since it can be sold whole and unbroken like a pudding or an egg custard, completely gelled in its container with no visible liquid. With nigari, soy milk turns into cloud-like curds that weep whey, called doufunao or tofu brains in northern China. You lose volume because of the whey, but the tofu has a better flavor, in my opinion.

Tofu makers often save the fresh curds as a treat for breakfast, dished out like congee with gravy, chili oil, and other savory toppings. Auntie’s doufunao specialty is eggs scrambled with fermented soybean paste (dajiang). The curds are buttery like the softest cheese and the whey is savory, drunk like a broth. A bowl of doufunao warms your stomach at dawn, while the remaining curds drain in the other room, waiting to be cut into tofu.

5

The further west you go in the country, the more you see douhua in a pairing, eaten as a staple with carbs.

Breakfast on a cold, drizzly morning in Guiyang is douhua mian (豆花面), which costs 10 yuan, less than 2 USD. I’ve never seen tofu served with alkaline hand-pulled noodles like this, relaxing in soy milk. I huddle at the table, pulling the noodles up, crossing the bridge from soup into sauce, and dunking them into the oily sauce to coat. Between bites you can nibble on fresh mint, salty peanuts, and pickled radish. The soy milk ends the meal, sipped from the bowl like a soothing digestif.

6

Douhua rice (豆花饭) is practically the same thing as douhua noodles, but rarely sold by the same breakfast vendor. This level of specialization boggles me.

In the tiny shop the metal tray comes with three bowls: fresh douhua, still soaking in their whey, hot steamed rice, and a dipping sauce. The soul of the meal is the chili sauce, made from hand-pounding soaked dried chilies and chili seeds with the addition of roasted peanuts, cilantro, and garlic. You can pick up this douhua with chopsticks— no slippery jello here. Dip the cloud of tofu in the sauce, coating it dark and red, and then hitch it onto the rice. Tofu, a spicy sauce, rice. One perfect bite.

Tofu in Guizhou is coagulated with suantang, fermented mustard green pickling juice, and the curds are larger and grainier, with receptive pores that soak up sauces. This is my favorite kind of tofu. It’s earthier and more human, still soft as curd, but not untouchable as a pudding. It weeps liquid and has a forgiving weight and lumpiness. We love it all the more for its cragginess.

7

Douhua mixian (豆花米线) in Kunming is rice noodles with silken tofu. It seems obvious, this pairing of soft, slippery tofu with soft, slippery noodles— why don’t we see this more in the States? I stir in the chives, the garlic oil and toasty crumbs of peanut, the salty fermented yacai.

Like boiled noodles or pasta, you wouldn’t eat tofu plain— it wants toppings, a shower of herbs, a liquid to swim in, a sauce to cling to. Douhua is really just free-form tofu, after all. Tofu that doesn’t have a shape, and is all the more delicious in its shapelessness, its willingness to be whatever the dish wants it to be.

So is douhua sweet or savory? The answer is yes.

There’s nothing more fun than a douhua party. All the potential to craft bespoke spoonfuls of bean curd happiness. Glorious, Hannah.

That all looks amazing! I would eat my way through a douhua trail. Looking forward to some douhua recipes in the next book 😆