Molten pocket tofu from the old town of Jianshui, Yunnan

coagulated with water from a 700 year-old well

In Kunming the sky was an inconsolable blue, the mountains capped with snow. But down in Jianshui, although the elevation is still 4500 feet, the clouds are pale and the air feels warmer; we pass fields of flowering youcai and freshly turned lines of red loam. When the train pulls into Jianshui station the platform is full. I follow the lines toward the manual verification exit, the escalators are waterfalls of feet, the place seethes with tourists. Is there no place in China without crowds? I just wanted quiet. I feel wrung out. But on the road the traffic thins, the driver hums. At the city wall he stops. Cars cannot enter the old city, he says. We get off and roll our luggage down the cobblestoned alley. The air is still and the sun is high, it smells like magnolia.

Jianshui is known for its deep wells and for its tofu. The two are related. Built in the Tang Dynasty over 1200 years ago, Jianshui retains many of its ancient walls and city gates (one of them resembles the Tiananmen gate tower in Beijing) and the old town remains busy with the traffic of ordinary life. Near the Jianshui Confucius Temple, the largest and best preserved Confucius temple in China, elderly locals sit on benches in the shade, peeling loquats. It feels like a Wednesday. All the visitors have been absorbed into small inns like ours, a minshu with five rooms. I browse the traditional purple clay teapot shops and watch the aunties grilling squares of tofu at the shaokao (barbecue) joints.

The largest and most famous well in Jianshui is Dabanjing, a few steps outside the west gate on a sloping road. Many of the 120 wells scattered around the city are still used to this day, with their stone openings (or well eyes, in Chinese) left with deep rope grooves. The water from this well is soft and sweet, it is best for making tea or cooking rice, a local says. He fills four plastic jugs and loads them onto his scooter. I dip a bucket into the water and drag the slack rope side to side, trying to make the bucket sink. The water doesn’t taste particularly special, but it’s cold and quenching, without any metallic taint. A fish shimmers in the deep water, a comma of vermillion.

Jianshui is located in a rift basin with karst landforms— large fractures or cave systems of limestone which can contain and transmit large quantities of water. The water should be similar to that of nearby Guilin, containing a lot of calcium and hard minerals, but since Jianshui is surrounded by high mountain ranges, its vast limestone acquifers capture large quantities of snowmelt, which are continually recharged. This gives the city some of the best water around, a deep supply that is resistant to intermittent drought. This particular well in Jianshui has been in use for 700 years.

The Zeng family, the owners of the Dabanjing tofu shop, tried to open a shop on the other side of the city and dug a new well, but discovered the water contained unpleasant-tasting minerals. The Dabanjing water, on the other hand, was soft and sweet with a lower pH, tapped into a source with the perfect combination of sedimentary minerals and mountain runoff. It almost did seem magical.

What happens if the water runs out? I ask. The owner shrugs. Then we stop making tofu, he says.

Before I came to Jianshui, I’d heard that their tofu is coagulated simply by using this special water, with no added coagulants. This is true, sort of.

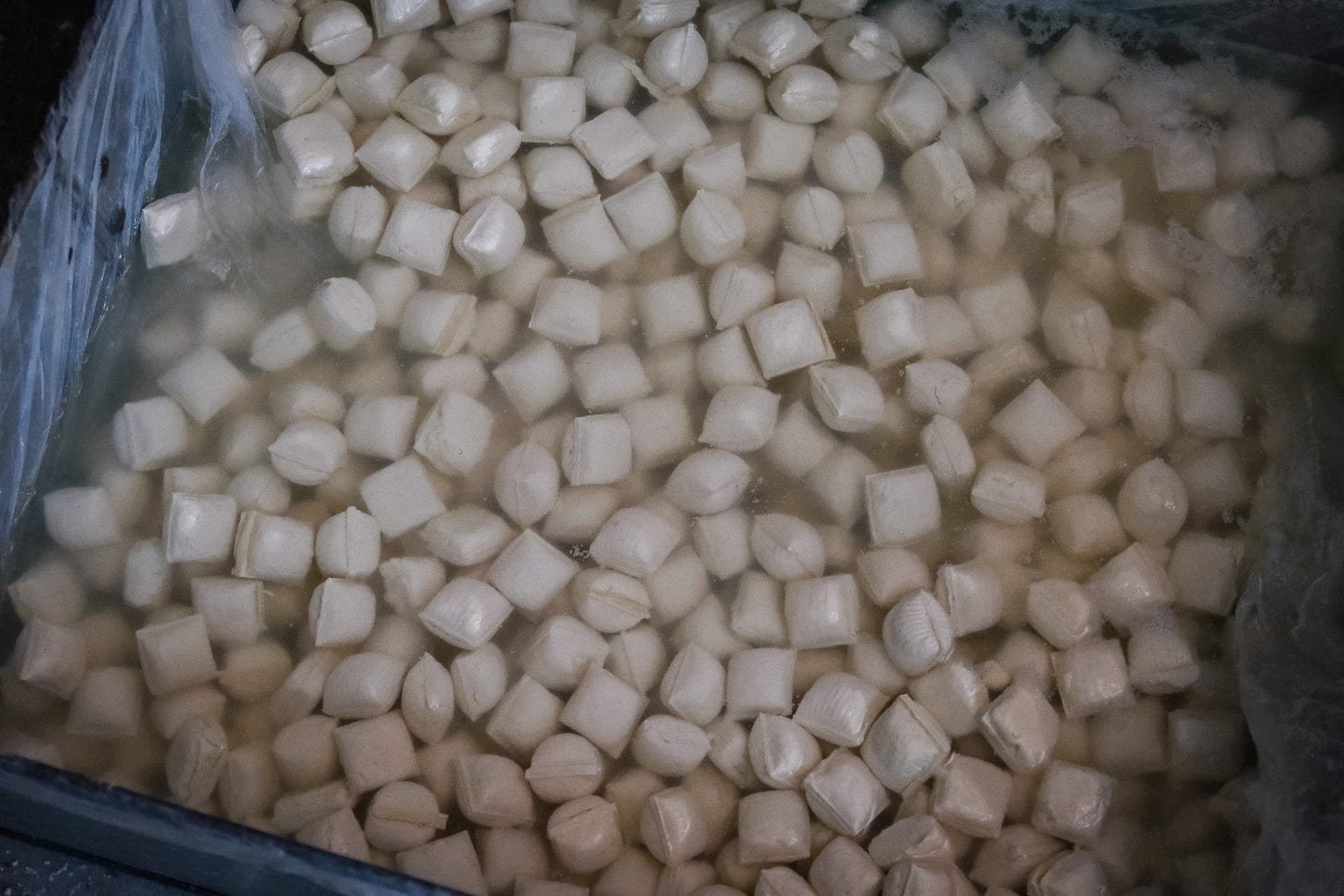

“We ferment the water overnight and use it to coagulate the next day’s soy milk,” the owner says when I ask, pointing to the vats of tofu curds soaking in a clear yellowish whey. I was stunned. Of course, they use the fermented, leftover whey. It all started to make sense to me.

In China, the most common two tofu coagulants are nigari or gypsum. Nigari (magnesium chloride), favored in northern China, is derived from seawater and produces curds with an earthy texture, delicate sweetness and superior flavor. Gypsum (calcium sulfate), the cheapest and most widely used coagulant in the coastal south, results in silky smooth, gelatinous curds.

However, neither of these are suitable for alkalinizing, the rapid separation of a flexible skin and molten interior necessary for pocket tofu and exploding juice tofu, the specialties of Yunnan and Guizhou. That’s where the third method of coagulation comes in— using lactic acid or acetic acid, produced naturally by lactobacillus, to curdle soy milk, much like yogurt. In Yunnan, tofu makers use leftover whey, since the warm temperatures allows the liquid to sour overnight. In Guizhou, tofu makers prefer suantang, the “sour liquid” left from pickling mustard greens. Both of these coagulating agents are free and perpetually renewable, and result in tofu that is slightly acidic.

Lactic acid makes an effective tofu coagulant, coagulating 55% of the soy milk’s protein versus 50%- 54.1% for gypsum. According to Tofu & Soymilk Production, A Craft and Technical Manual (2000) by William Shurtleff and Akiko Aoyagi, "The reason that people do not precipitate tofu curds at the relatively acidic isoelectric point (pH 4.2, the point of minimum nitrogen and protein solubility) and then neutralize it is that the proteins tend to redissolve as the pH moves back up to neutral."*

However, this “redissolving” effect is exactly the texture desired in Yunnan molten tofu. With alkaline treatment, which I’ll talk about later, the tofu curds melt into liquid over the intense dry heat of a charcoal grill, a skin quickly forms on the exterior, and the outside temperature becomes much higher than the inside. The liquid is contained by the sturdy skin.

My working theory: The combination of Jianshui’s soft well water with a lower level of alkalinity, plus the acidity of fermented whey coagulation, results in the distinctive texture of Yunann tofu.

*Shurtleff and Aokyagi do not mention Yunnan, only citing Japanese, Vietnamese, and Indonesian tofu, which makes sense as tofu traditions in China were little known at the time of writing.

Before I leave the tofu shop, I watch the five women wrapping tofu by hand, each seated at their own station like seamstresses. The individual parcels of tofu lie on wooden trays, rows of squares so uniform I thought they were formed by machine. This is the choudoufu 臭豆腐 or xiaodoufu 小豆腐, tofu fermented for 4 to 5 days in the sun until they dry and turn chewy over a charcoal flame, with the subtlest hint of cheese. Jiejie scoops some wet curds with her palm into a three-inch cloth, pulls in the sides of cloth like tucking in a baby, and squeezes the little round pat to remove some moisture. As she sets it down, she unwraps the next tofu, places it on the nearby board, and uses the same cloth to scoop fresh curds, a movement so practiced she barely looks down. I usually make 3000 a day, she says.

The pride of Jianshui is that their tofu can’t be replicated anywhere else. “You can take the same method and reproduce it another city, but because of the well water, the flavor will always be slightly different in Jianshui,” the owner says. He adds, “We have the perfect weather for making tofu.” Blessed with high elevation and mild weather, nights in Jianshui are warm enough to sour the whey overnight. The hot sun allows racks of tofu to dry out rapidly, and the low humidity keeps the fermenting tofu from spoiling.

In the last few months I’ve been researching the alkaline treatment of tofu— traditional methods found in Yunnan and Guizhou province that transform soy milk curds even further. Similar to nixtamalization in masa, this change in pH tenderizes the soy proteins and results in unusual textures like molten lava, custard and exploding juice interiors (爆浆, 恋爱豆腐). Paired with tea-leaf smoking and charcoal-grilling, the alkaline imparts the tofu with develops deep, pretzel-like colors and sulfuric flavors reminiscent of ramen noodles, egg, and bacon. For example, huidoufu 灰豆腐 in Guizhou, is made by rubbing and tossing suantang tofu with wood-ash from charcoal stoves, a natural alkali. The tofu becomes semi-dried, and after rinsed with water, develops a hollow interior and a deeply flavored, chewy skin that absorbs sauces.

I am saving most of the details of this research, but the main point is that tofu goes beyond the simple coagulation methods known in the west, with textures that are baffling and exciting, but for locals of Yunnan and Guizhou, none of it is new.

Back at the tofu shop, we decide to eat breakfast at the self-serve tofu bar, for 6 yuan a person (85 cents USD). The freshly coagulated curds are served as douhua. I eat two bowls, the first bathed with brown sugar syrup, the second topped with savory fermented douchi (the original natto), stinky tofu brine, chili sauce, garlic oil, and chili flakes. The curds are creamy and gentle, with the slightest tang.

I soak puffed crackers of fried tofu skin in my bowl and then dip the fried tofu in a dry spice mix, a blend of roasted chili flakes, Sichuan peppercorn, caoguo (ground black cardamom), MSG and salt. The tofu is good fried, with the density of a chicken nugget, but I prefer it grilled over a hot charcoal flame, where the exterior blisters into a chewy skin and the center puffs up. For that, we head to barbecue. (Pt. 2)

i want to try 包漿豆腐 and 灰豆腐!

Loved the walkthrough of the process, the photos of the well, and the 路边摊. Just discovered your Substack, it’s already bringing back such fond memories — thank you for that!