Some geographical context:

Guiyang is located in Guizhou Province, bordered by Sichuan to the north and Yunnan to the west. It is subtropical in climate and high-altitude, and receives the least sunshine of any major city in China. (On average, Guiyang gets 1150 hours of sunshine per year; Seattle’s 2100 hours is downright balmy in comparison).

Outside the airport, taxis stalled like roosting chickens in the mid-morning lull, waiting for rides. A few drivers walked around soliciting passengers in the drizzle, but most were resigned to smoking in their car, their windows rolled down. I woke up from a disorienting nap and a good cry on the plane and arrived feeling tender and a little lost, but the air hit me at once, cold and damp, sharp and reviving with the smell of gasoline and citrus, cigarette smoke and frying grease.

Guizhou province is one of the largest chili pepper producers in China. Chilis were once foreign to the country, like tomatoes and potatoes, but after 400 years of culinary use the spicy, smoky pepper found its way into nearly every local dish, becoming indispensable to Guizhou flavor. In hubs like the city of Zunyi, farmers sell dried chiles and chili products to traders in tons— the Guizhou market makes up a tenth of the global total and one-sixth of China's, an annual trade of around 7.2 billion yuan worth ($1 billion) last year.

The old thrill of finding lunch

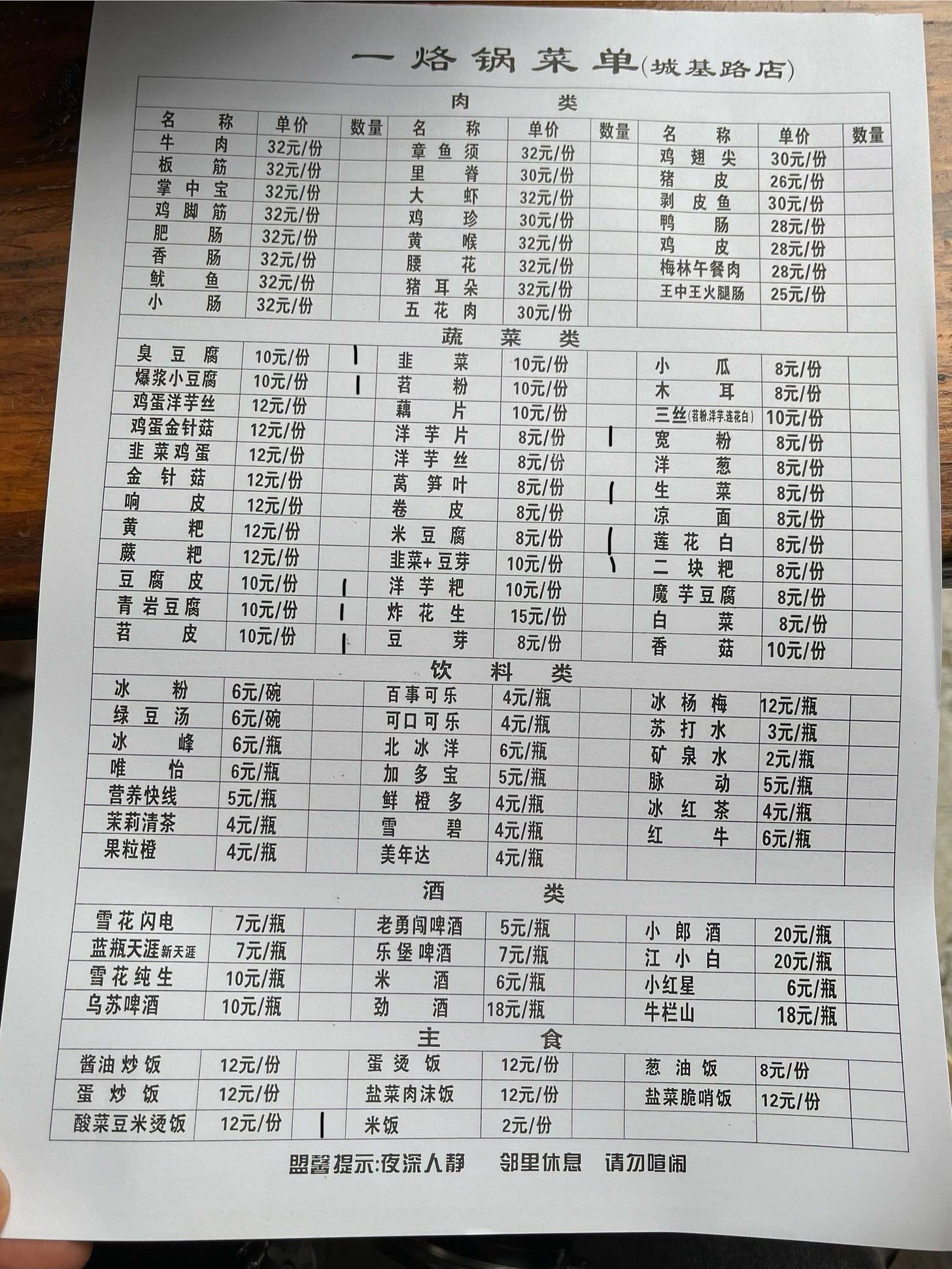

I joined my friends George and Jamie for lunch. Like any Chinese meal, Guizhou barbecue (luoguo 烙锅) makes more sense to eat with a group. Traveling alone, you’re all too aware of the limitations of budget and stomach, but ordering for three people is a lot more fun.

We checked off all the tofu varieties: paodoufu 泡豆腐 (slabs of tofu dried in the sun and then popped under hot stones), choudoufu 臭豆腐 (a strong and leathery stinky tofu), baojiang xiaodoufu 爆浆小豆腐 (‘exploding juice’ tofu with a molten interior), jueba 撅耙 (chewy, translucent noodles made from the dark starch of bracken fern roots), doufupi 豆腐皮 (glossy strips of tofu skin), qingyan doufu 青岩豆腐 (a tofu from the Qingyan village, eggy with alkaline), and midoufu 米豆腐 (rice tofu that’s tender like a starch jelly).

Each table came with a black clay griddle, domed like a stomach. The server lit the pot until it was searing hot, and when the chives and leafy greens had wilted and the tofu was smoking we began to eat, nearly burning our tongues, everything was oily and delicious, we scraped potatoes and rice squares off the center with a metal spatula, there were glorious crispy edges.

For Chinese meals, a feeling of celebration is closely tied to visual abundance— the idea of courses feels stingy compared to a whole spread, all at once. More plates arrived without order or ceremony, we dumped them on the clay griddle and went back and forth for more sauces. I felt the giddiness of a child (or an adult at an open bar). There is no rule to the sauce proportions but instinct, the pleasure of curating to your own preference.

Guiyang is a city of underground walkways and pedestrian malls. To cross a wide street we often had to descend, navigating escalators and constricted pathways of subterranean traffic just to emerge a few hundred feet away on ground level. For someone who’s directionally challenged, all you hope is that you don’t come out on the same exact street corner. Malls have B, B1, B2, B3, B4, even B5 levels, each plaza with their own bathroom attendants, Starbucks, and Uniqlos. At night, food stalls are the hubs of activity, bright with blinking neon signs.

People hustle hard in the Guiyang economy. Even brick-and-mortar restaurants would post servers outside their storefronts to wave signs and solicit pedestrians with specials. Vendors would record themselves hawking and then play their voices from portable speakers without any self-consciousness. In every corner, people were making and selling food for a living, and I realized this was an instinct that ran everywhere in China, an aggressive resourcefulness derived out of necessity.

Tofu is, in essence, making something out of very little. In the West we are obsessed with chefs and people who make food, and often glamorize the craft behind traditional dishes and products, but many times these foods were just ways to survive. In a landlocked province like Guizhou, without the flow of money and goods into ports like the coastal cities, people lived off subsistence farming. Tofu was invented to make soybeans edible and nutritionally available.

Guizhou has the most varieties of tofu than any other province in China. Over hundreds of years, people were equally inventive with rice, potatoes and even bracken fern roots (撅粑), pounding and collecting their starch and turning them into noodles and jellies and cakes, cooking them in dishes that are now specialties. These traditions of subsistence, over time, have become foods of regional pride.

I can smell the BBQ and hear the sizzle, it's all so well-described.

So thrilled this newsletter exists. Me and my partner LOVE your cookbook (we had the sesame noodles yesterday). I have literally never seen so many varieties of tofu. London is slowly (very slowly) becoming more tofu friendly (I found tofu skins the other day, a huge win), but this is next level.