Yunnan pickled cabbage and cold-dressed tofu skin 'shoots' 豆笋

Biking to open-air markets pt. 2

Read Pt. 1 here: Baizu wok cooking

The next morning we ride down to Yousuocun, a village close to Dali’s Xihu/West Lake (“Xihu” seems to be a popular name for a lake in China, like Mill Creek). People are in good spirits, trudging down the shaded sidewalk with bags of produce. Car horns blare. Vendors unload crates from the trunk of vans: thick celtuce crowned with purple leaves, fresh rice noodles, crocks of fermented vegetables.

Leafy greens appear in abundance during the winter. Vendors make several varieties of pickles, using mustard greens, radish tops, napa cabbage, and the common long-stemmed cabbage, gao gan cai. The winter air is dry and the sun is hot— perfect for drying vegetables and sanitizing vessels for fermentation.

I buy a crock of fermented yan cai to take back home. This is the most ubiquitous Yunnan pickle, made with gao gan cai. The leafy green tastes like a cross between lettuce and napa cabbage, with long, crunchy stems and a mild, sweet flavor without any bitterness. The fermented veg is called shui yan cai (水腌菜 “water pickled vegetable”) because of the juiciness of the cabbage and the tangy liquid packed into the jars. It’s a crunchy accompaniment to cut through richer dishes like stewed meats or rice noodles.

How to make shuiyancai (Yunnan pickled cabbage):

Soak the bunches of the greens overnight. Rinse thoroughly in clean water, 4 times. Bundle up and hang in the sun to dry. When there is no longer any dripping water, it’s ready. Best to prepare this before winter solstice.

Ensure that there is no oil during any of the process. Cut 500g of the greens into 1/2-inch pieces. Cut a carrot and a daikon radish into shreds. Lay them out to dry. Mix everything in a large bowl with 7g salt, 2g huixiang fen (ground fennel or fennel seeds), 2g Sichuan peppercorn and white pepper, a handful of chopped fresh chilies, and a spoonful of brown sugar. Sterilize the jar with baijiu (strong liquor). Pound the mixture into a crock— the liquid should cover the top of the cabbage. Tighten the lid and wait 3-5 days to ferment. When it’s at your preferred sourness, refrigerate. Will keep for up to a year.

A few kilometers south we cross a bridge. The village is quiet, there’s not a human in sight. The bridge is wide and simple, with steps and posts fitted of stones. Dry grass grows out of the cracks like untrimmed hair.

"This is old!” W yells. “It's very old!" He drops his bike and sprints back across the bridge. I don’t get the excitement; we’ve already passed plenty of old structures in the last few days.

I read the plaque, which informs me that the bridge, 天衢桥, was constructed in 1487. 1487??? My brain is spinning and searching for reference points, trying to comprehend something it really can’t. This bridge existed three centuries before the existence of the United States of America. It’s still structurally intact after five hundred and thirty-seven years of use, even though the people who built it are long gone. Most of the posts are worn down to smooth nubs, but one of them remains intact. It’s an elephant, with a distinct carved trunk.

(Elephants are not common in traditional Chinese carvings. This one must've been influenced by traders on the Tea Horse Road, part of the Silk Road connecting Yunnan province to Nepal, Burma, and India).

This little bridge somehow survived both natural and human disasters. It outlived the inexorable, irreparable destruction of the Cultural Revolution. It was left alone by modern developers. It sits mostly unused, in a sleepy village, wearing slowly away under the wind and the sun.

We're all silent as we continue riding, crossing west into the looming mountains. The air grows cold, the shadows sharper. I suddenly feel very small and very silly. My self-important thoughts are shrunken in scale. Even these trees that line the road are much older than me.

At the next market, I see a variety of tofu I’ve never seen before. Each slab is orange, dry to the touch and bendable like a book cover. “What’s this?” I ask the vendor. “It’s delicious!” he says. “How about this one?” I point to the shrink-wrapped slabs. “It’s tasty!” he says. We guffaw.

He finally tells us that the tofu is made with turmeric (jiang huang), fried until the color deepens and the skin blisters. The saddle-brown ones are regular dougan, tofu curds compressed to a tender, bouncy firmness, brined with soy sauce, then lightly smoked on racks.

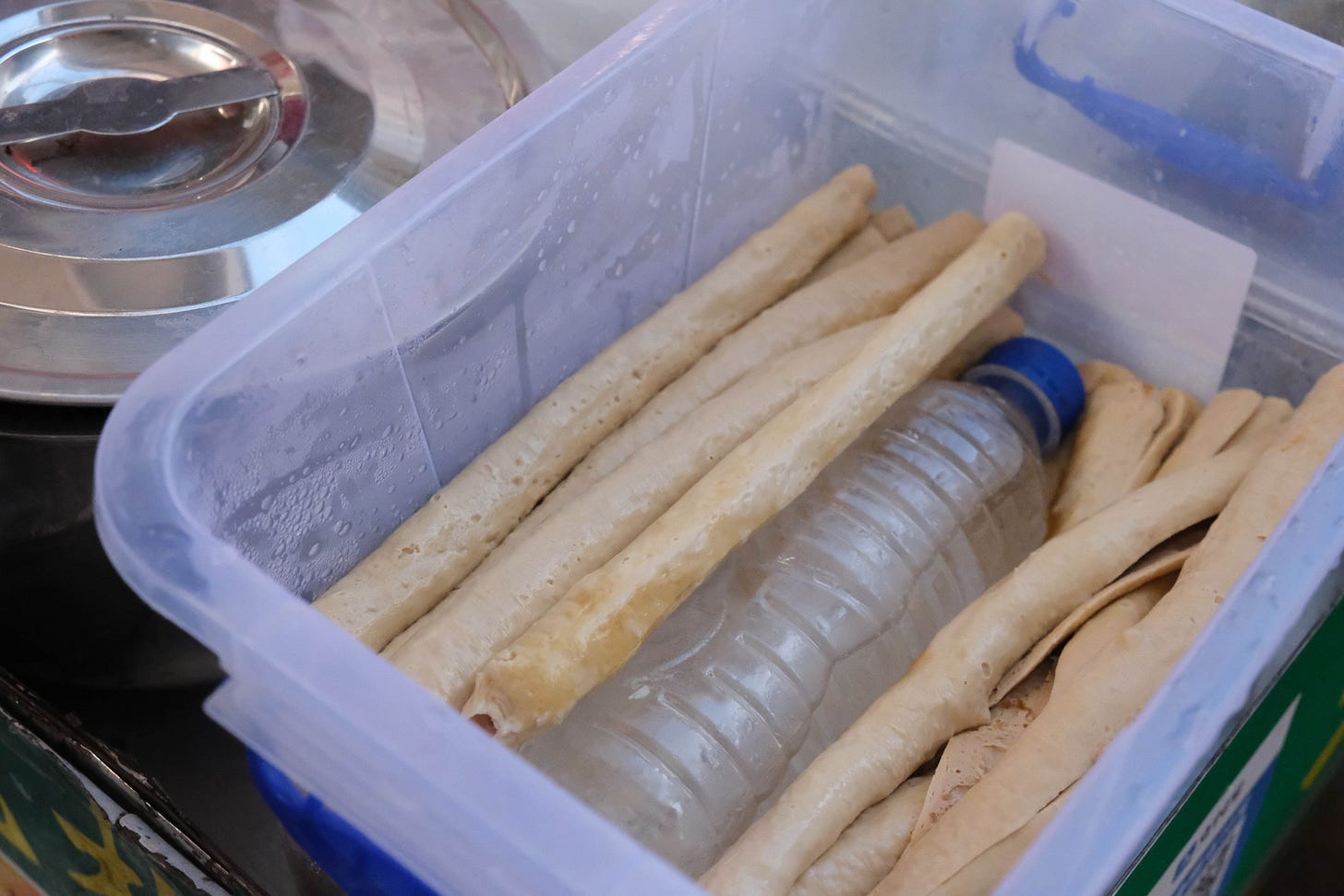

Another vendor I meet sells dou sun, 豆笋 (literally “bean shoot”), a variety of tofu skin. It’s called a few other names, depending on where you are in China.

dou gan 豆杆, ‘bean rod’

dou bang 豆棒, ‘bean stick’

dou jin 豆筋, ‘bean tendon’

dou gun 豆棍, ‘bean stick’

Dou sun is originally from Kaijiang (开江) in Sichuan province. It’s made by wrapping freshly pulled tofu skin around a rod. Each layer of tofu skin melds with the one underneath, forming a thin, hollow ‘tendon’ of protein. When the required thickness is reached, the rod is slipped off and dried. The color often has a gradient from darker yellow in the center to pale. I’ve only seen dou sun completely dried, like fu zhu (腐竹), and those must be rehydrated before slicing up for stir-fries or salads.

While we watch, the vendor slides the tofu into a bowl with the flat side of her knife, adding a generous ladle of garlic oil and scorched chili oil, fresh chilies, peanuts, scallion, and cilantro. She pours a dressing from a tea kettle (tastes like soy sauce, pinch of sugar, MSG, with plenty of black vinegar). I stuff the bowl in a bag for our lunch later, and while it knocks about my pannier the tofu skin soak up all the flavors of the sauce. Delicious.

A final variety of tofu: niupi dougan (牛皮豆干 “leather tofu”). I’ve seen this in a few markets in Dali: essentially very thin dou gan, cut into fun shapes and tossed in a marinade. The common seasonings are sesame oil, chili oil, garlic oil, five-spice, or teng jiao (Sichuan peppercorn). A great snack to eat with beer.

Please more! MORE! 😊

Hello Hannah, have to be brief as taking meal to my soon 93 yr old mum. Who is stoically independent.

Love your travelogue so so much, especially about bridges and all the great food.

Will read in more detail layer.